“Nothing to Conceal”

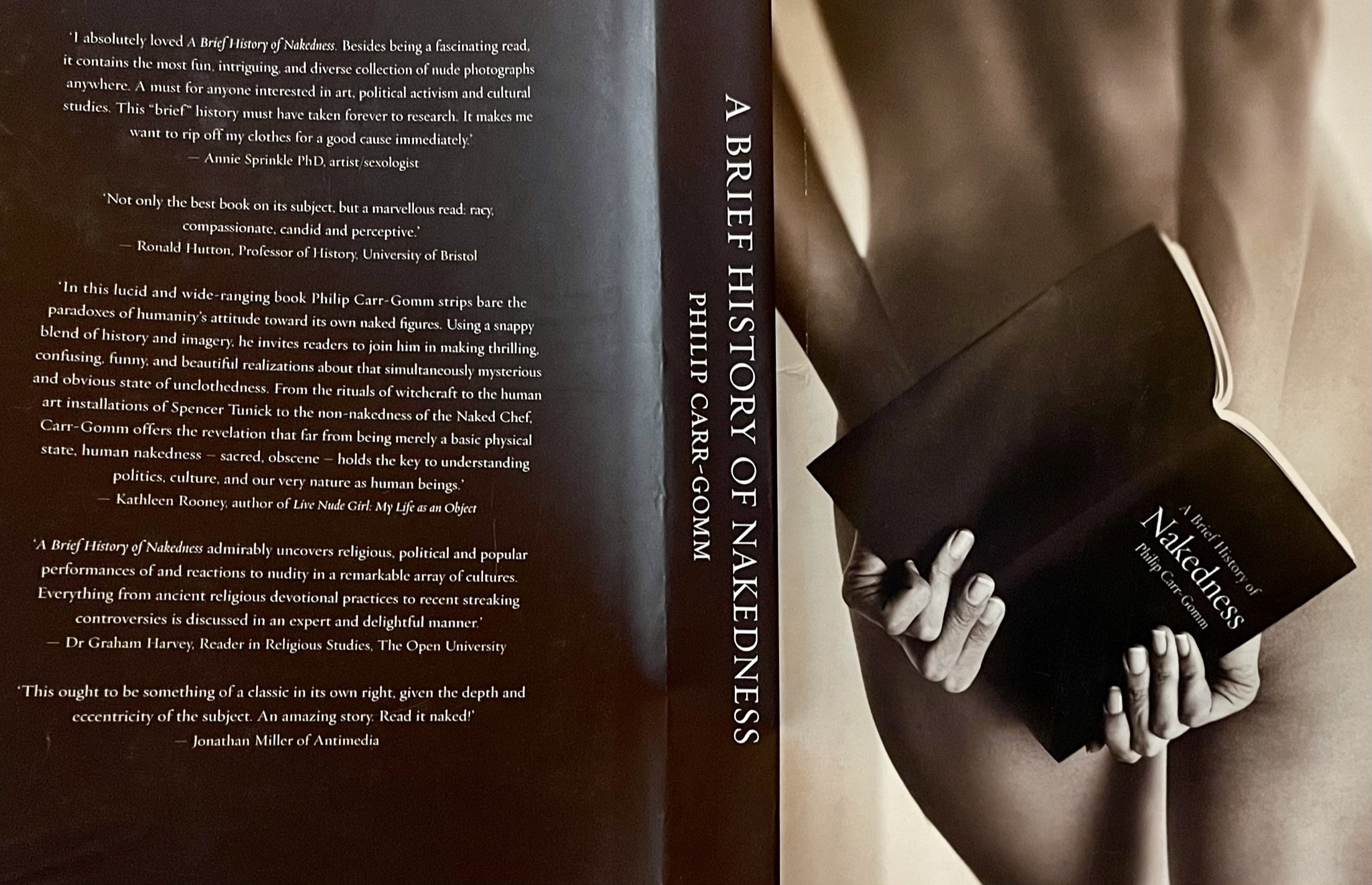

The following text is reproduced from “A Brief History of Nakedness” by Philip Carr-Gomm, with kind permission from the author. A fascinating academic review of the book, including commentary on the history of naturism, is available here.

When it comes to our feelings about nakedness, contradictions and paradoxes abound. In religion nakedness can signify shamefulness and a lust that must be conquered, or it can symbolise innocence, a lack of shame, and even a denial of the body. In the political sphere, nakedness can symbolize raw power and authority, or vulnerability and enslavement. These contradictory associations help to explain our complex and often conflicting responses to the subject and why it offers such a fertile ground for artistic and philosophical exploration.

Two great streams of influence have moulded modern Western attitudes: one deriving from the classical pagan world, the other fed by the influences of the Judaic and Middle Eastern worlds. The latter cultures most frequently associated nudity with poverty and enslavement. The rich and powerful wore clothes and ornaments to demonstrate their wealth and prestige while prostitutes, slaves and the mad went unclad. In distinction, the Greeks elevated the naked human form to the ideal, and statesmen would be sculpted naked to demonstrate their likeness to the gods. It is no wonder, then, that the Christian inheritance, drawing as it does upon both classical and Judaic inspiration, has developed such an ambiguous set of attitudes towards nudity.

Nowhere is the juxtaposition of contradictory responses to nakedness more obvious than in the realm of politics, where the most powerful people on earth require the protective 'clothing' of armoured limousines and guards, and the least powerful can hold a government or corporation to ransom by simply threatening to remove their clothing.

Nakedness makes a human being particularly vulnerable but in certain circumstances strangely powerful, which is why it has become so popular as a vehicle for political protest. By exposing the human body, protesters convey a complex message: they challenge the status quo by acting provocatively, and they empower themselves and their cause by showing that they are fearless and have nothing to hide. But at the same time they reveal the vulnerability and frailty of the human being.

“Government, like dress, is the badge of lost innocence.”

-Thomas Paine, Common Sense

In Plato's Gorgias, Socrates speaks of a legend that he has decided to accept as the truth. In the old days souls were judged at the end of their lives by Cronos, who sent the good to the Isles of the Blessed, and the bad to the unpleasant prison of Tartarus. The process was flawed, however, since the souls were judged just before they died and while still clothed. Zeus fixed the problem by arranging for people to be judged naked once they had died - by judges who were also naked. Nothing got in the way of the truth.

Socrates acted on his principles, and in The Apology, like a judge who, gazing into the souls of the newly dead, needs to be naked himself, he strips before the Athenians to confront them with the truth about their injustices. Further west the same idea was being used by clan chieftains and kings in Ireland, who would stand naked before their people to prove that they were unblemished and that they would engage in no dissembling. To stand naked before someone is the simplest way of showing you have nothing up your sleeve, and there is something reassuring and wholesome about a politician who is unashamed to be seen in the nude.

When Churchill was visiting the United States and staying at the White House, president Roosevelt once found Churchill striding back and forth across his room completely naked, puffing on a cigar as he dictated to a male secretary. As Roosevelt tried to beat a hasty retreat, Churchill called him back, saying 'The prime minister of Britain has nothing to conceal from the president of the United States.’